Why Triads Changed Everything for My Rhythm Playing

(And How You Can Start Using Them Today)

When I finally started using triads in my rhythm playing, everything clicked. Chords stopped feeling like boxes and started sounding like music. I wasn’t just grabbing shapes, I was choosing voicings that made sense. I could finally connect open chords and bar chords in a way that felt musical, not mechanical. And once I learned how to move triads around the fretboard, my rhythm parts opened up. They had direction. They had purpose. They sounded like me.

The truth is, if you want to be more than just a chord-strummer, triads are non-negotiable. They’re the building blocks of great rhythm guitar. But knowing the theory isn’t enough, you need to see how these shapes live on the fretboard. In this post, I’ll walk you through what triads are, how to find them in any key, and how to start using them to create clean, connected chord progressions that sound like real music. If you’re ready to break out of the rut and start playing rhythm parts that actually work, this is for you.

What Are Triads?

Let’s start from the beginning. A triad is a type of chord made up of three different notes. That’s it. Just three.

If you’re already familiar with open chords like G, C, or D, you’ve been playing triads without realizing it. But when you learn how triads are built, and how to play them in compact shapes, you gain control over your rhythm playing in a whole new way.

Every triad has three parts:

The Root (this is the note the chord is named after)

The 3rd (this is what gives the chord its major or minor quality)

The 5th (this note gives the chord stability)

Let’s look at a few examples:

G major triad: G (root), B (3rd), D (5th)

G minor triad: G (root), B♭ (flat 3rd), D (5th)

You can already see how one note makes the difference between major and minor. The B becomes a B♭ in the minor version. That single note shift changes the feel of the entire chord.

You can use the notes of a major scale to find triads. For example, in a C major scale (C D E F G A B), the C major triad uses the 1st (C), 3rd (E), and 5th (G) notes of the scale. That’s the formula: take the root, skip one note, then grab the next, skip another, then grab the third.

If you’re wondering whether this is just a theory exercise—it’s not. Knowing how a triad is built helps you find it anywhere on the fretboard. And once you know the pattern, you can use it in any key.

Types of Triads (Fully Explained)

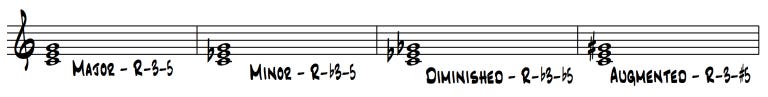

There are four main types of triads. Each has its own distinct sound and use.

1. Major Triad

Structure: Root – Major 3rd – Perfect 5th

Sound: Stable, bright, and resolved

Formula: R, 3, 5

Example: G – B – D

To build it, start from the root. Count four semitones (half steps) to get the major 3rd. Then count three more semitones to get the 5th. You’ll land seven semitones above the root, which gives you that perfect 5th.

2. Minor Triad

Structure: Root – Minor 3rd – Perfect 5th

Sound: Darker, sadder, more emotional

Formula: R, ♭3, 5

Example: G – B♭ – D

This one changes just one note from the major triad: the 3rd. It moves down one semitone (one fret on the guitar). Everything else stays the same.

3. Diminished Triad

Structure: Root – Minor 3rd – Diminished 5th

Sound: Tense, unstable, used for suspense

Formula: R, ♭3, ♭5

Example: G – B♭ – D♭

Start with a minor triad and lower the 5th by one semitone. Now you have two minor 3rds stacked. The result is a more tense, dissonant sound that’s useful in transitional or dramatic moments.

4. Augmented Triad

Structure: Root – Major 3rd – Augmented 5th

Sound: Bright, uneasy, unresolved

Formula: R, 3, ♯5

Example: G – B – D♯

This time, you start with a major triad and raise the 5th by one semitone. It creates a dreamy, floating sound—often used in jazz or as a tension-builder in pop or rock.

Every triad you ever play is one of these four. Once you know how they’re built, you can find them in any key and start using them intentionally.

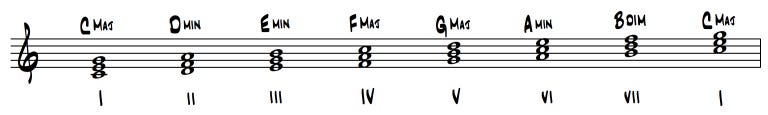

Triads in a Key

Every major key has seven notes. You can build one triad from each note by using the 1–3–5 formula on that scale degree.

Let’s take C major as our example. The notes in the scale are:

C – D – E – F – G – A – B

Now let’s build a triad off each one:

C major: C – E – G (I)

D minor: D – F – A (ii)

E minor: E – G – B (iii)

F major: F – A – C (IV)

G major: G – B – D (V)

A minor: A – C – E (vi)

B diminished: B – D – F (vii°)

That gives you the foundation for building progressions inside any key. You’ll start to recognize common movements like I–IV–V, or ii–V–I, which show up in thousands of songs.

You’ll also start to hear how these chords relate to each other and create emotional movement.

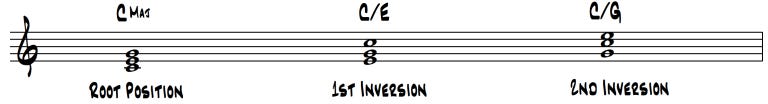

Inversions: The Secret to Smooth Transitions

Inversions are simply different ways to arrange the same three notes of a triad. Instead of always starting with the root as the lowest note, you can put the 3rd or the 5th on the bottom.

Here’s how it works:

Root Position: Root – 3rd – 5th (C – E – G)

1st Inversion: 3rd – 5th – Root (E – G – C)

2nd Inversion: 5th – Root – 3rd (G – C – E)

These are still C major triads, but they sound and feel different. On guitar, each inversion has its own shape. You’ll often see these used in slash chords. For example:

D/F♯ = D major chord with F♯ in the bass

C/E = C major chord with E in the bass

Inversions are powerful because they allow you to move smoothly from one chord to the next. Instead of jumping around the neck, you can just change one note and keep the rest in place. That kind of movement is called voice leading.

Voice Leading and Why It Matters

Voice leading means moving as few notes as possible from one chord to the next. This creates smoother, more musical transitions. It’s how professional rhythm guitar players make their parts sound connected and intentional.

Here’s an example:

C major = C – E – G

A minor = A – C – E

Notice that two notes (C and E) are the same. You only need to change one note (G becomes A). When you play triads with this kind of awareness, you create a sound that flows rather than jumps.

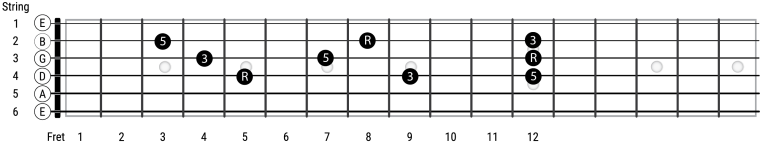

Guitar is a visual instrument. Learning where your triads live on the neck and how to move between them is what makes this voice leading approach possible.

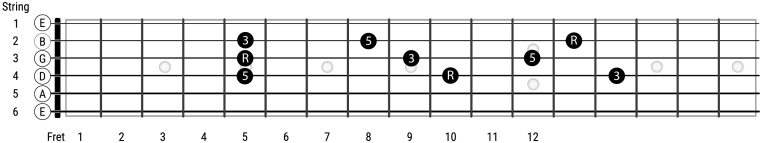

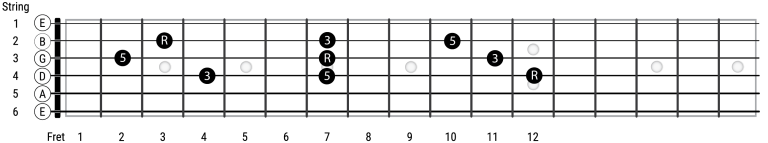

Where to Play Triads on Guitar

The guitar has six strings, but the magic starts happening when you isolate triads onto sets of three adjacent strings. That gives you a clear structure to work with.

There are four main string sets:

6–5–4

5–4–3

4–3–2

3–2–1

Let’s take the 4–3–2 string set as your starting point. On this string group, you can play any major triad in three ways:

Root position

1st inversion

2nd inversion

Start by learning these shapes for a G major triad. Then try the same for C major and D major. These three chords make up the I–IV–V progression in the key of G.

Now here’s the practice:

Play a G–C–D–G progression using the root position shape of G as your starting point

Play the same progression starting with the 1st inversion of G

Play it again starting with the 2nd inversion

Each version moves differently across the fretboard, but the harmonic content is the same. This helps you internalize how triads move and how each inversion feels.

Once you’re comfortable with that, repeat the same process on the other three string sets. This gives you a complete map of triads across the fretboard.

Wrapping Up

When I first started playing guitar, I could handle a few open chords and some bar chords. That got me through a lot of songs, but I always felt stuck. I didn’t sound like the rhythm players I admired. Something was missing.

That something was triads.

Learning triads gave me control. It gave me variety. It gave me a framework to understand how chords work and how to move through them musically.

If you’re serious about becoming a well-rounded rhythm player, you need to understand triads. You need to be able to see them, play them, and hear them in your head. That’s when your rhythm playing stops sounding like shapes, and starts sounding like music.